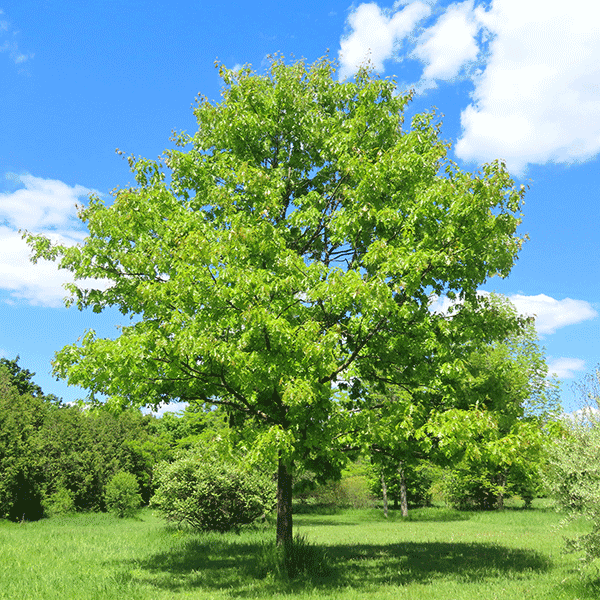

Why two oaks? Though red oak was requested for the arboretum, we discovered after the planting that a similar sharp-lobed leaved species called pin oak was installed. This is not necessarily a negative. Pin oak is a native and has some fine attributes. However, our recommendation for urban planting in Halton Hills would be the versatile red oak. (We hope to have a red oak planted at the arboretum soon.)

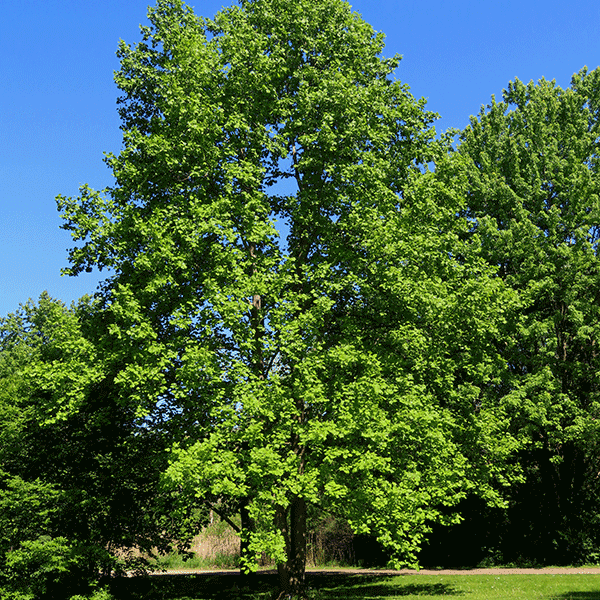

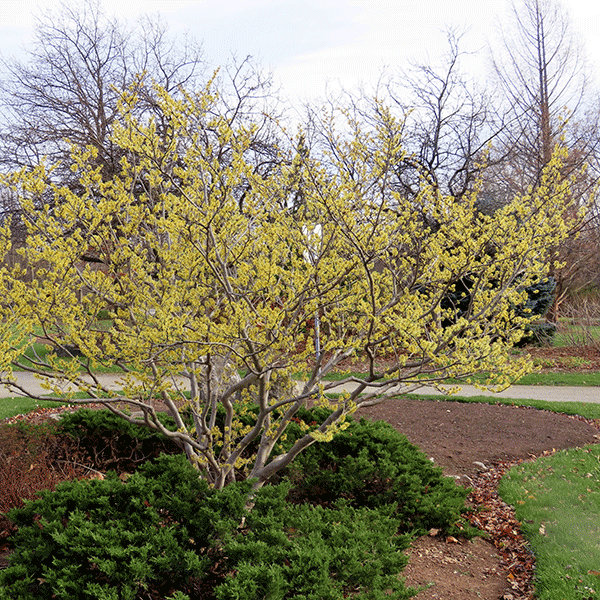

Pin oak is a rare species in Ontario, found primarily in Niagara Region and Essex County. They have more exacting soil requirements than red oaks. Their species name “palustris” means “marshy” or “swampy”, providing a clue as to where this tree likes to grow in nature. Although there is some natural variation in the species, most pin oaks like some acid in the soils they grow in. Most Halton Hills soils are neutral to slightly alkaline pH.

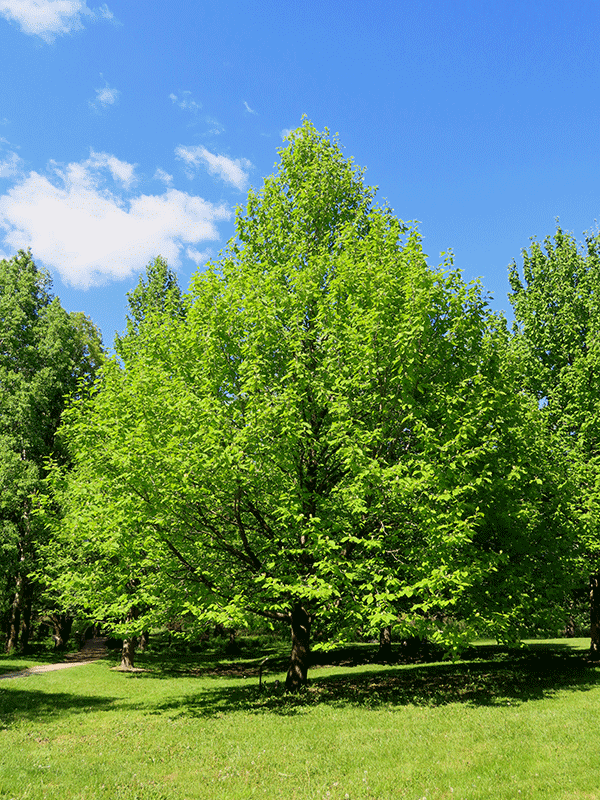

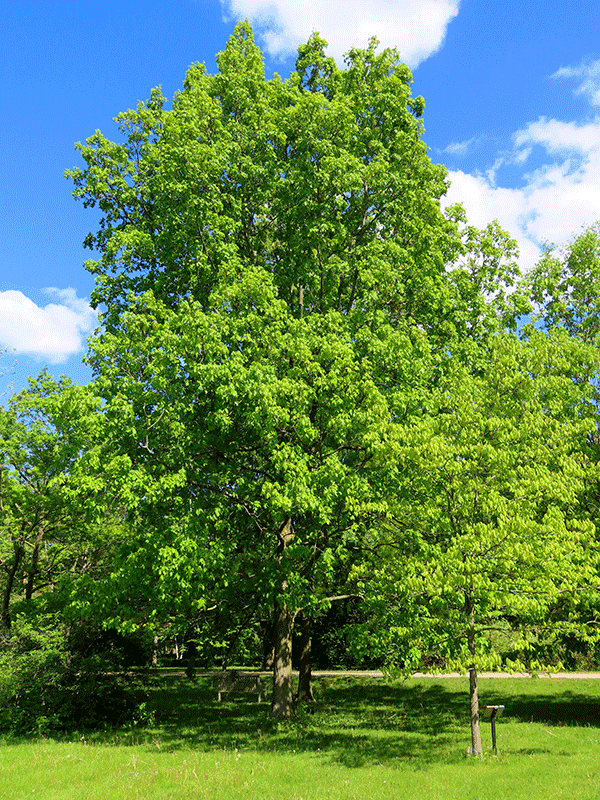

Red oak on the other hand is simply one of the most versatile trees we have, growing everywhere in Halton Hills and throughout southern Ontario. It can thrive in all soil types and is impervious to environmental conditions, growing in forests and as solitary specimens in agricultural areas.

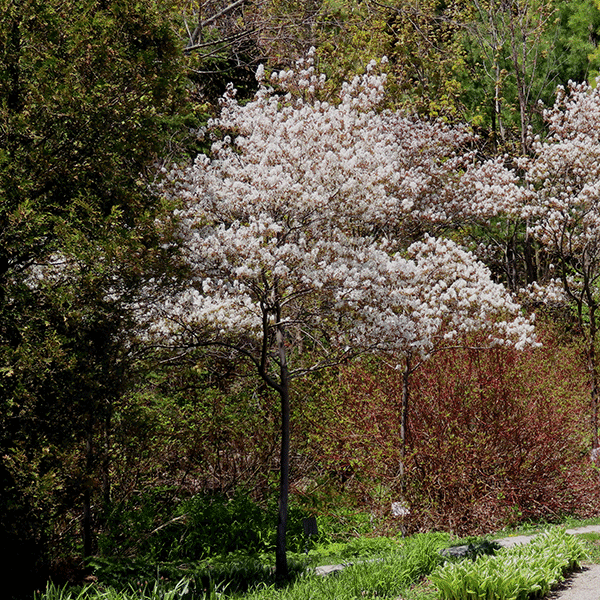

Virtues: Both species are beautiful. Both grow into strong, long-lived trees. Both offer fine russet foliage colour in autumn. Pin oak is unique among oaks for its pyramidal shape in its first few decades. Red oak grows into a statuesque muscular tree that will dominate a neighbourhood for many generations. It is a standout in our urban or natural environments.

Wildlife Value: All oaks are prime food for native caterpillars which our songbirds appreciate. The best place to look for the incomparable scarlet tanagers is among oaks, where the adults gather food for their young. All oaks also produce acorns, a valuable food source for birds like blue jays and red-bellied woodpeckers and for small mammals.

Needs: Both pin oak and red oak will appreciate as much sun as you can offer. As mentioned, pin oak is more particular to soil type (see above). Red oak on the other hand will thrive just about anywhere. All oaks are attacked by LDD moths. (But so are many other tree species!) Even a major infestation of LDD caterpillars is unlikely to harm a mature tree, but with smaller specimens some control is advisable.

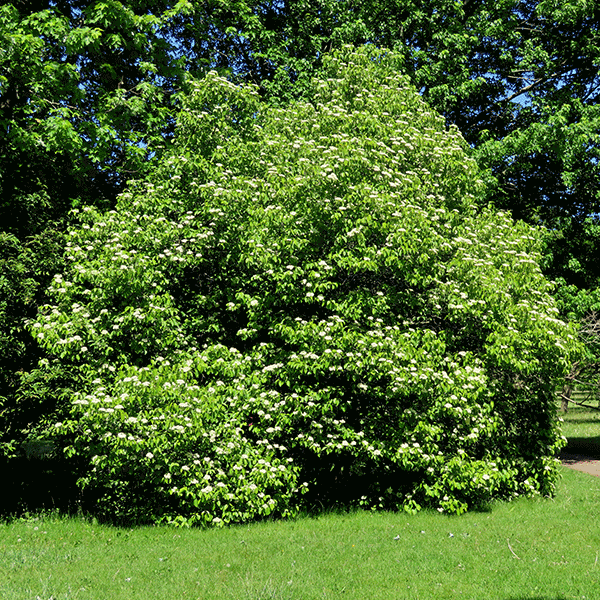

Local examples: Red oak is one of the most common Halton Hill’s trees. Big and bold, they are easily found in area woodlands. Their abundance becomes evident in the autumn. After other deciduous trees have lost their leaves red oaks stubbornly hold on to theirs for a month or more. Mature urban red oaks can be found at the Georgetown Fairgrounds and Greenwood Cemetery in Georgetown.

Pin oaks have been planted sparingly by urban forestry departments. Two fine pyramidal young specimens can be seen along the bike path behind the Gellert Centre in Georgetown. Some boulevard plantings of pin oak in this area have not fared as well, demonstrating a yellowing of the leaves called chlorosis, caused by insufficient iron in alkaline soils.

Special Note: To reiterate, our recommendation is that you select red oak for an urban yard in this area, not pin oak. Red oak is also much easier to find at area nurseries.